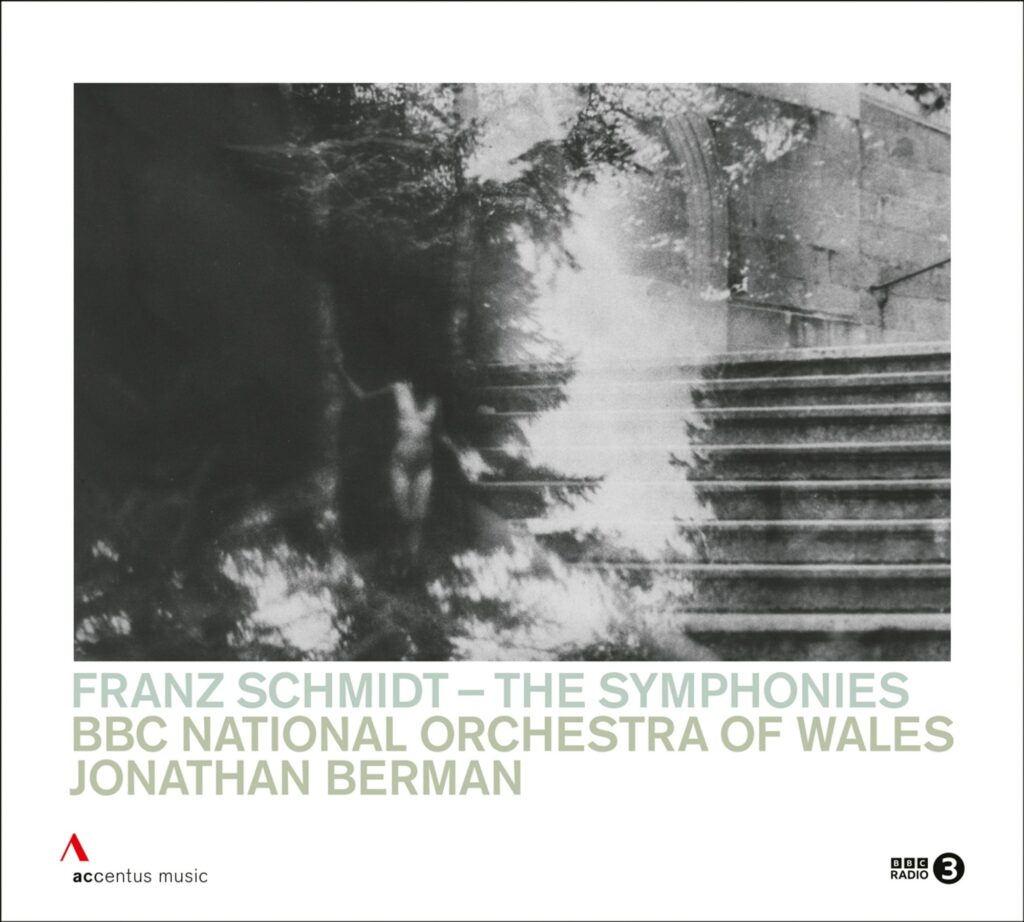

Conductor Jonathan Berman has recorded the complete Symphonies of Franz Schmidt with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales for Accentus Music. The recordings were reviewed here. Norbert Florian Schuck spoke with Jonathan Berman about this project, Franz Schmidt’s music and more. The following conversation took place in the rooms of the Franz Schmidt Musikschule in Perchtoldsdorf. The music school possesses many furnitures from the household of Franz Schmidt himself as well as his own pianoforte.

The recording of Franz Schmidt’s piano playing mentioned in the conversation is the first performance of Alfred Einstein’s completion of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart’s Rondo for pianoforte and orchestra in A major K 386 which took place on 12 February 1936. Franz Schmidt was accompanied by the Vienna Symphonic under the direction of Oswald Kabasta. The performance was broadcasted from Austria to the United States, where it was recorded by an unknown radio listener. A collector, who had come into possession of the recording provided it to Norbert Florian Schuck, who showed it to Anthony and Maria Jenner of the Franz Schmidt Musikschule Perchtoldsdorf. The recording was never published commercially.

[Der Dirigent Jonathan Berman hat mit dem BBC National Orchestra of Wales für Accentus Music die sämtlichen Symphonien von Franz Schmidt eingespielt. Die Aufnahmen wurden bereits an dieser Stelle besprochen. Norbert Florian Schuck sprach mit Jonathan Berman über dieses Aufnahmeprojekt, Franz Schmidts Musik und mehr. Das Gespräch fand in den Räumen der Franz Schmidt Musikschule in Perchtoldsdorf statt, in welchen sich zahlreiche Möbelstücke aus Franz Schmidts Wohnung befinden, ebenso sein Klavier.

Bei der erwähnten Aufnahme, in welcher Franz Schmidt am Klavier zu hören ist, handelt es sich um die neuzeitliche Erstaufführung des Rondos für Klavier und Orchester A-Dur KV 386 von Wolfgang Amadé Mozart in der Vervollständigung durch Alfred Einstein, die am 12. Februar 1936 durch Franz Schmidt, begleitet von den Wiener Symphonikern unter Oswald Kabasta, stattfand. Die Aufführung wurde von Österreichischen Rundfunk in die USA übertragen, wo sie von einem unbekannten Radiohörer mitgeschnitten wurde. Dieser Mitschnitt gelangte in den Besitz eines Sammlers, der ihn Norbert Florian Schuck zur Verfügung stellte. Dieser wiederum machte Anthony und Maria Jenner von der Perchtoldsdorfer Franz Schmidt Musikschule mit der Aufnahme bekannt. Der Mitschnitt ist nie kommerziell veröffentlicht worden.]

TNL: Let’s start the conversation! What were your impressions when you came to Perchtoldsdorf the first time?

JB: I had made contact with Maria Jenner [headmaster of the Franz Schmidt School of Music in Perchtoldsdorf] when we released the CDs of the complete Franz Schmidt Symphonies. However, not really knowing what to expect I came to explore and found a treasure trove of things relating to Schmidt, even including his piano. I was fascinated by his piano as I had written about how the sound of his piano playing give us clues into how to interpret his music in the booklet of my recording. There is this certain approach that Schmidt has in creating his harmonic language out of counterpoint, and we can play and perform it in a way so that it really comes to life. I was thrilled when I played his piano, as it completely confirmed my impression of the sound of his piano playing, and thus his music, which I had found in his notes and throughout my research.

In preparing for the recordings of the Schmidt Symphonies I had studied all of his sketches which I could found, and I had even seen some counterpoint lessons he gave: there’s a book of lessons he gave to Ludovit Rajter, and also some counterpoint exercises of Susie Jeans, which are in the British Library.

That was a real moment for me, because in these exercises Susie Jeans writes a perfect counterpoint, but Schmidt corrects it, not that they are wrong, but his corrections are constantly saying, “This can be more beautiful, this can be stronger, this can have more gravitational pull of the contrapuntal melody.”

So these exercises show Schmidt’s search for beauty and artificiality?

I wouldn’t use the word “artificial”. I’d say he was looking for lines which were “more organic”, “more natural”. Think of the sentence from Goethe which Schmidt liked to quote when he was asked how he writes his music: “I sing how the bird sings” [“Ich singe, wie der Vogel singt”]. He was committed to his music sounding natural, and desired that each sound or tone creates the next ones naturally and organically whilst everything is connected at a fundamental level. It is almost as if Schmidt doesn’t write his music, but once it starts the music creates itself, which is something I searched for in these recordings to try and make the performances sound like the music was creating itself.

I have extrapolated a lot from this idea – even the photographs I commissioned for the CD covers, taken by my great friend here in Vienna, Kristina Feldhammer. They’re all analogue photographs created on film and then in the dark room, which I think mirrors Schmidt’s music (and something we have tried to find in the recordings as well). Kristina’s photographs create a sense of tactility – you can almost touch them, they are not hidden behind a modern shiny veneer which is absolutely my approach to bringing Schmidt’s music to life.

Look at her photo of the Strudlhofstiege steps, there is this sense of architecture, which she combines in the dark room with photographs of nature, of the Wienerwald and of the surrounding areas creating an image which is trying to find in this architecture, nature and the human, or the divine and the earthly. Additionally then, of course, they’re all self-portraits, which creates a sensuality, drawing parallels to the turn-of-the-century Klimt-esque, Schiele-esque, Schnitzler-esque exoticism and eroticism, which we see in the music of Strauss, Wolf, Zemlinsky (actually many composers of that time) and of course, most importantly, all through Schmidt’s music.

Coming back to Schmidt’s piano, I was really thrilled that I found that playing his piano matched what I had found in his music. For instance, certain keys which are traditionally expected to be “bright keys”, like E major… If you look at a passage in Strauss, in Beethoven, in Brahms – even although it’s quite rare for Brahms to write in E major –, it’s a slightly brash key. In Mozart’s operas E major is often almost militaristic: lots of sharps, everything’s a little bit raised and tense, and somewhat bright.

In Schmidt’s music that’s not the case. Playing his piano you hear that it’s the mellowest, softest E major which while it ‘proves’ nothing, for me just adds to weight to the characteristic of the keys which I find in his music.

Schmidt was of course one of the absolute greatest pianists, so his connection to the piano is important. Leopold Godowsky, when asked who was the best pianist of the time, said: “Well, the other is Franz Schmidt.”

Did your imagination of Schmidt as a piano player influence your concept of the recording?

At the time of recording the symphonies I did not know that there was a recording of Schmidt playing the piano (although I searched long and hard for one) so I developed an an idea of how Franz Schmidt might have played the piano, from writings about him, and above all from listening to recordings of other pianists of the era in particular the other students of Schmidt’s teacher Leschetizky, such as Leopold Godowsky. Closest to Schmidt’s playing though – as it was described by his contemporaries – were the recordings of Ernst von Dohnányi.

Interestingly they grew up in Pozsony (Preßburg) which is now Bratislava, only a few years apart from each other. Both played organ in the same church – the next organist of this church was Bartók. They all spoke Hungarian as a first language, Slovakian and German. Still there are a few people in Preßburg-Pozsony-Bratislava, who have this trilingual culture and live this multicultural approach to life. I recently spoke to Adrian Rajter, the son of Ludovit Raijter (a student of Schmidt’s who recorded the complete symphonies), who is a very passionate linguist and still believes in this three-cultural world.

Anyway, I learned a lot about the piano playing of Schmidt from listening to Dohnányi. I’m absolutely not a period performer at all, and I don’t think there is ‘authenticity’ in how to perform music ever. But what I can do is to research as much as I can, so that when I look at a written piece of music and I can use this research (for instances from recordings) to try and open it up, to try and find a key into the music, and discover how to translate the music from the page into sound.

Firstly there is transparency: all of these players play so that you can hear all the voices. There’s none of the heavy post-Soviet piano playing. It didn’t even exist in their minds. So in all the voicings of the chords – thirds are softer, fifths are a bit stronger, tonic bass notes are quite strong always, inner voices are very prominent – there is a sort of transparency of sound while still being resonant and sonorous and singing.

There is a great flexibility with tempo, which comes out of the harmony. It’s not a ‘Chopin-esque‘, or a ‘modern-Chopin-esque’, rubato which functions in order to expresses something about the performer or as some virtuoso trick designed to differentiate yourself from another player. It really is part of the music, and we can find examples of this style of tempo flexibility in the scores of Schmidt’s contemporaries.

Look at Mahler, or Schoenberg, or Webern, or Berg: Every bar, every two bars there’s some tempo marking, there’s an expression marking describing the changing and modulating tempi. With Schmidt’s scores it is very different: mostly there’s just one tempo at the beginning. And it’s very interesting: None of his sketches have tempos or dynamic markings and very rarely are his sketches orchestrated, although occasionally you see a instrumentation written in works around a certain phrase or line. For instance, in the Fourth Symphony very early on in the sketches is a trumpet solo, so he already was thinking in that way. But the drama of the music comes out of the notes he chose, out of pure counterpoint, and the rhythms…..

…the balancing of tension and resolve of harmony…

Exactly! In such a nuanced fashion, even the layering of multiple tensions and resolutions such as having one phrase over 16 bars, one over eight bars, and there is something else going on over four bars… I’m not talking about regularity, but about layering of different narratives so create (literally) deeper music.

Sometimes the music content is about deep or profound ideas as well (such as the 4th symphony), but depth doesn’t have to relate to the content, in music ‘depth’ can just be if there is a lot going on at one point.

To finish the story about the piano:

So now, thanks to both you and Maria [Jenner] I have now heard Schmidt playing, and it is almost exactly what I expected, but more! It’s more imaginative, more fantastical!

If you hear this recording of the Mozart, every gesture is taken care of in a very small scale way, but also as a view of a larger structure. Nothing is repeated the same. It’s what everyone always said about Schmidt: He never played the same thing twice. So if he played the same piece again he would play it differently, not in an improvisatory or extemporising sort of way though, but finding other opportunities which are presented by the notes. This was all because he understood the structure and underlying architecture of the music so well.

The piece is one big moment for him: In this special case the moment is 8 minutes long! In our digital age, you know with Formula 1 talking about 0.01 of a second, we think: “Well, that’s a single moment.” Our zeitgeist is all about discovering the smallest possible denomination of everything – in this case what constitutes a singular event. Actually, though ‘the moment’ in music can be much longer. A whole symphony can be a single moment. Schmidt’s Fourth Symphony is a single ‚moment’, I think the Third as well. The second consists maybe of two ‘moments’, and the first maybe of four. For me there is definitely some time travel needed to recover this idea of expanding ‘the moment’ and connecting more under a single idea (such as the Gestalt Principals of therapy [of Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler following Christian von Ehrenfels] do, or Heinrich Schenkers musical analysis do – both from the same time as Schmidt) rather than our modernist was of dissecting until the smallest is found.

Schmidt’s playing uses the structure, playing within its framework, with incredible discipline he found such freedom, fantasy and imagination. When you listen to this recording of him playing, the more you listen, the more you find, and that’s I find with his own music.

I’ve been working on his music now nearly 20 years, and in a great depth for seven years: recording the Symphonies, editing them, learning them, bowing them, spending hours and hours – and I still find more! Even more – I still am in love with his music, (which is not always the case)! There’s some very good music that you spend six months learning, and then a week with an orchestra, and then you’re happy to leave it for a few years. I always want to go back to Schmidt’s music. After a performance the first thing I do is: I open the score and want to explore more……

So every time you come back to Schmidt, it’s a new journey, a new experience for you?

Absolutely! It doesn’t have to be a hugely different journey, I re-experience it every time, but without ignoring the journeys I’ve already been on. I have a very short attention span and I get bored very easily; so, if I tried to just do exactly the same thing again (because that’s what I did the time before) I would get bored, and well before anyone else.

That’s the special sign of quality of Schmidt’s music?

Yes. Although, of course there are other composers who’s music gives you new experiences every time you engage with it. But I do think there is something very special in Schmidt’s music – you can hear it in his piano playing: the sheer vivaciousness, the delicacy, the gestures, the sort of gravity… I don’t mean gravity as in weight, I mean the gravitational pull of a gesture. It’s like a dance.

Considering the recording, I found it interesting that Schmidt criticised his teacher Leschetizky very much for his, as he said, abusive rubato playing. He himself is completely free in tempo, but it is every time in the right way!

The hidden question which you didn’t ask is: What would Schmidt think of my recordings which definitely have quite free tempi? But let’s leave that to the side for the moment.

I think there’s some very interesting things about composers and how they react to their own music, or how they play their own music compared with how composers play other people’s music. They are all connected, but often it’s like a Venn diagram: They don’t quite line up. When you talk about vibrato, when you talk about tempo flexibility, when you talk about rubato, it’s very easy to criticise somebody. It has become a fashion in our times to understand this criticism as a statement of existence or not existence as opposed to a criticism of quality: just think of of the comment of Leopold Mozart that vibrato shouldn’t sound like a meowing cat, a statement which many people have taken to mean that Leopold Mozart hated ALL vibrato (or even more extremely that vibrato didn’t exist) – as opposed to him just saying that vibrato should sound good not bad! So Schmidt criticised Leschetizky about his excessive rubato from which you can only understand that Leschetizky’s rubati didn’t work for Schmidt.

I have a theory about why that might be: When you hear Schmidt’s playing, or you read about his approach to performance, the most important aspect for him is that everything comes out of the music – out of the notes. However, we don’t know much about Schmidt’s relationship with composers where melodic inflection is one of the main modes of expression – Chopin for instance.

We don’t know what Schmidt thought of Chopin’s music or of playing Chopin – or at a least I don’t… Unfortunately, we don’t have a recording of Schmidt playing Chopin. Chopin writes music where the structure underlying the whole piece is simple, but the interest of the music is what happens on a single beat, coloured in very refined ways. So it’s very easy to stretch each moment, and move it around showing off all the minute colourings and small scale relationships.

If you apply that style of rubato then to Mozart or Beethoven, to the larger structures, the large scale harmonic structures of a movement, or the varied repetitions – so when a first subject comes back again, or when a second subject comes back, but in the tonic, not the dominant – the small scale rubato of Chopin just doesn’t work. When you hear someone like Dohnányi playing Beethoven – because there are recordings of him playing Beethoven –, it’s so free, but within this very structured framework.

So, to answer your your hidden question, I have interpreted or translated Schmidt’s criticism of other people of playing with bad rubato, meaning that for Schmidt they weren’t connected to a deeper underlying structure. And whilst I take a lot of tempo flexibilities, I actually try – I don’t know whether that comes off – to create them as a flexible tempo, not rubato. Rubato has this sense of stealing tempo from one moment to give to another. But when performing Schmidt (or Bruckner or Beethoven and many others) I have in my head a sense of pulse and subdivision, and that the tempo is expanding or contracting – a bit like a concertina. You have one movement, one pulse through the piece but, the tempo, the (modernist or absolute) metronome mark might change.

My flexibility often happens over whole phrases. So one phrase will go slower or faster than another phrase. This idea of time keeping is very pre-digital, pre-atomic-clocks, pre-idealised sense of regular time. So it’s much more about felt time: If a pulse feels the same, it is the same.

As a practical example look at the Third Symphony: the first subject of the first movement. It comes four times over the whole movement, and for me I play each time at slightly different tempi to create a sense of a phrase over the whole movement hopefully creating a sense of structure over the whole movement. The first time (right at the opening) is the first time you have heard the material, then you get the second time which is the repetition of the first time (repeat of the exposition), it has to say something different!

It reacts at this point to the music which has been heard before.

Exactly, and you recognise it but it can’t say the same thing twice! So, I take it slightly faster (and phrase it slightly differently connecting it under a longer phrase). Then at the beginning of the development, there is one with a diminished type harmony, which for me has to go slightly slower, because it’s a moment of questioning. The recapitulation then seems to comes out of nowhere, and can come back to a much more relaxed state. Finally the last manifestation of this first theme begins the coda. It is in a very foreign harmonic area and functions as the lowest point of the movement and so for me the slowest point of the movement. I hope that this will create a real journey and relationship between the opening phrase and the beginning of the coda.

You mean a moment of complete relaxation?

Well, it’s not complete relaxation but it’s a moment of complete unknowing of where you’re going, and it’s created by the harmony, the texture, and the orchestration. This music is different the last time we hear it in this movement, and what I have done is I’ve tried to make clear and amplify those characteristics I find in the music, so that as a listening, it is clear that the music is not just carrying on you have a feeling of “Oh what’s going to happen? Oh – what’s – going – to happen?”

You may criticise my performances, say that they are too obvious, say that I lose people, you may say my tempo flexibility is too much. But that’s fine, I want people to listen and react, and if they feel that this is the case, it’s great!

So the beginning of the coda is the moment you create the type of tension which makes the people curious about the second movement?

Exactly! And that for me is much more tempo flexibility as opposed to rubato, although there is some freedom in the phrases. I have no idea what Schmidt would think of it. I, of course, hope he would like it.

I do work a lot with living composers though, and again this idea of authenticity or correctness just doesn’t exist. Performing music is all about life, it’s about giving music life and drawing your listener on a journey! So I think Schmidt would have been very pleased with our recordings.

Of course, when the composer writes something, it is performed, it is out in the world, and it begins living on itself like the child begins to live without the parent.

Yes, you can affect it, and you can hope for it and be a part of it. It’s the same with making recordings. I mean, these are the first recordings I’ve made. I’ve done sessions for the radio, but a recording is not a live performance. It has to have life, but again you have to let it go.

I, of course, hope people put this on a really good stereo or really good headphones, they sit down, they take 45 minutes, and they listen to the whole thing in that space. I can’t control that, and I shouldn’t control it. People might hear it on Youtube, they might hear it in the Metro, they might hear it in the airplane, they might hear 20 minutes of it, they might turn their radio on in the car. And I hope that, whatever happens, the music grabs them, and they go: “Oh, this is interesting!”

But, like with the composer when composing, I feel that a performer should give everything they can to the recording, but then you have to let it live its own life.

Was it clear for you that you want to make your recording debut with Franz Schmidt, when you started to work as a conductor?

No, not at all. I love recordings, I have a huge record collection at home. It’s so big, I can’t even fit it in my house: CDs, LPs, even tapes… I love the medium of recording, and I think it can be incredibly powerful. What was very clear for me right from the beginning of my career was that I wanted to record meaningfully. The more you know about the record industry and what has been recorded, the more you question: “Why do I record this? Is there a real need for this new recording?”

There are different ways of answering that question, and different reasons. For me they had to be musical reasons, and it had to be something to really affect an audience, to draw them into the love which I feel for the music. So there was a moment, where I was thinking that it would be an interesting project to make a recording, and I was sort of looking around for what might be a meaningful project to record. I found Schmidt much earlier, I’d been performing some of the Symphonies, and I really felt that the music was underplayed, underrepresented by this point. (This was before Paavo Järvi had announced his cycle.) I felt that through the performance and through my study of Schmidt’s music there was a lot in the music which I could bring out to draw people into the music. I felt it was music very close to me, and the more I questioned it, the more meaning I found behind the idea of making a recording of it and of building content around the recording: the Franz Schmidt Project which I’ve set up! So I’ve been interviewing other musicians, putting a recordings list up online, and trying to stimulate performances.

So the Franz Schmidt Project and your plans to record the Symphonies grew organically from the same source?

Yes, they grew out of this sort of meaningfulness that I could find in recording his symphonies. I also was very clear that I didn’t want to make a recording just for me, or for my own career. I felt that recording Schmidt’s symphonies had real musical and societal reasons.

When I was starting to think about this project I approached lots of people and asked them whether they knew Franz Schmidt. Some people didn’t know him at all. Fine, that’s a great opportunity to bring the music to them! But the people who did know it, many of them had had an experience with Schmidt early in life, in their teenage years, where his music had really opened them to the power of music. If we can get people involved in, we can play music that has that power, and if we can show a commitment and a dedication to it then that’s a very positive thing. So I felt there was a personal reason to do it, there was a societal reason to do it, a musical-societal, not a sort of extra musical.

I felt that there was something in the music that I could draw out, which just perhaps hadn’t been drawn out before, either because some of the really great recordings had been back in the 60s, 70s, 80s – you know: the Ludovit Rajter [Symphonies No. 1–4], the Libor Pesek [Symphony No. 3], even the Zubin Mehta recording [Symphony No. 4]. The Neeme Järvi recording [Symphonies No. 1–4] has a certain viewpoint of all of the pieces, and I felt like it was worth presenting a different viewpoint. It’s not like doing a Beethoven cycle where almost every viewpoint has been covered.

You have mentioned Rajter and Järvi and other famous interpreters of Schmidt of the past. Are there some of them who you consider to be references for you?

Not really, no, because I think Schmidt’s been very lucky on that there aren’t really bad recordings, and it’s a testament to the depth of the music that many different viewpoints can work. There’s also a more recent cycle with Vassily Sinaisky from Malmö, which is good and the complete cycles of Rajter, Neeme and Paavo Järvi, Luisi, Sinaisky, they’re all absolutely valid viewpoints – I don’t say that with any cynicism. I do think that Mehta, Pesek, and Bychkov [Symphony No. 2], who did one Symphony each, are possibly the most interesting of the recordings, but the idea of a reference recording is a very specific thing, but I don’t think any of these are that, but they are all valid viewpoints.

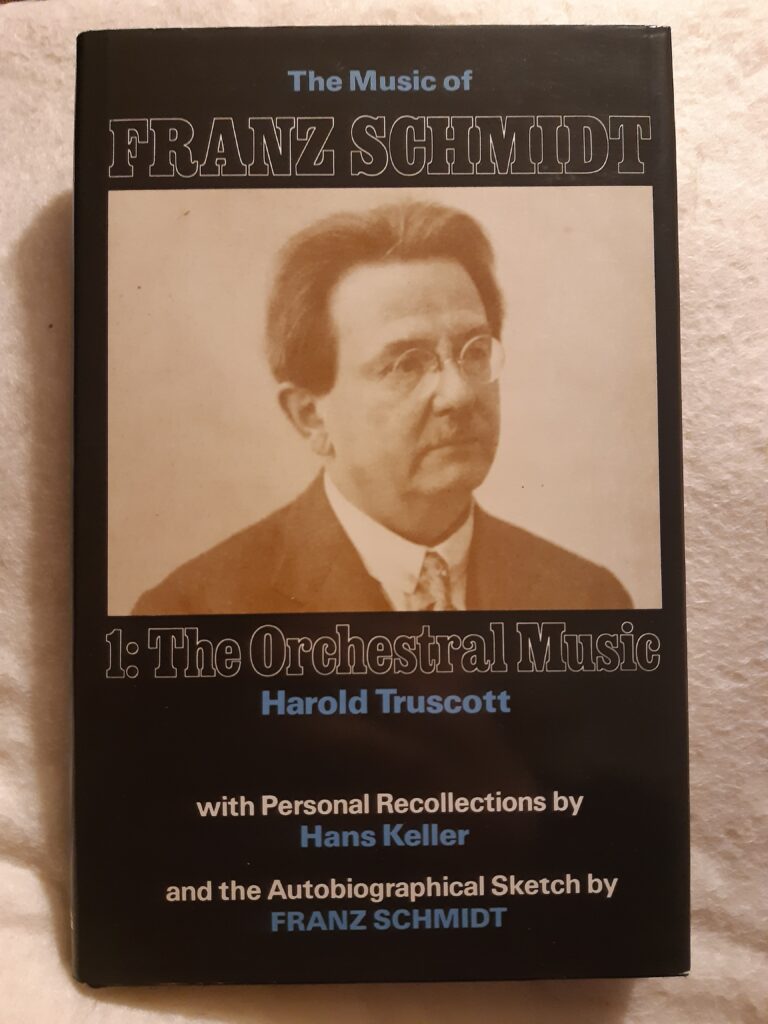

One of the most important writers on Schmidt was British composer Harold Truscott. Would you say that there is a specific tradition of Schmidt in Great Britain?

To be honest it doesn’t feel like there is. Very little Schmidt is played now, at least. Until a few years ago I’d never heard his music live in Britain. The Vienna Philharmonic brought the Second Symphony to the proms about 5 years ago, and then the Berlin Philharmonic brought the Fourth to the proms about 4 years ago. But before those two works I’d never heard any of Schmidt’s music live in the UK and I only know of two orchestras who have played his symphonies recently (as I have conducted all those concerts!).

I know that there have been various recordings over time, and I’ve done a lot of research into the radio broadcasts that you can find, which are often very interesting. For instance Alfred Walter did a whole set of broadcasts of the Symphonies with the BBC Northern, which you can listen to at the British Library. Simon Rattle performed the Fourth Symphony, there is an archive broadcast.

Of course, Franz Welser-Möst conducted the Fourth Symphony with the LPO in a very good recording, very different performance from anyone else, which is fascinating. He also conducted Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln at the proms.

Truscott’s book on Schmidt is very good, and Truscott was a wonderful composer, very original, but also it’s very interesting that his music sounds like he could have studied with Schmidt. The other person who came to the UK and was a great supporter of Schmidt was Hans Keller. There are some criticisms and some musicological essays by him which are all quite brilliant. He wrote on Schmidt’s music along with much other music, and he was very involved with the BBC. When he was there he pushed Schmidt’s music, which is why we have some of the broadcasts. But I wouldn’t go as far as to say that there is a particularly British tradition of performing Schmidt’s music.

One of the things that I was very keen to do with the BBC Welsh Orchestra was to discover a Viennese – or a more central European – tradition of playing. We worked really hard at that, and I am proud of the results we got: for instance, making a more resonant tone, not playing too loudly, often slightly slower bow strokes, taking real care over the connection of lines, particularly in instruments like horns where you might not expect real, true legato over big intervals.

Schmidt writes wonderful horn lines, and I don’t think it’s too silly to say that you have to imagine yodeling, which is a real legatissimo multi-tessitura line. When you think of Ländler and yodeling you think of a sound world with transparency, but without losing depth of sound, also a profound understanding that lightness doesn’t have to be a lack of seriousness, which I believe is a very Viennese or central European idea. This ties together the slightly softer, warmer, resonant sound and along with more transparency so that the inner voices coming out, and so on. We really worked very hard at trying to find that. We tried and now it’s up to you to decide how successful we were!

The ‘Viennese tradition’ is wonderfully complex. To start with, it’s not just an Austrian tradition. Vienna has always been, and particularly in Schmidt’s lifetime, a multilingual, multicultural city.

Schmidt himself was not just Austrian, but also Hungarian and Slovak and there are many Hungarian elements in his music. The interesting thing about Schmidt is that for him the Hungarian music, the ‘Hungarisms’, that he writes are not just exoticisms, they are a founding element of style.

So within his Hungarian style he still writes nuanced music.

So to add this Hungarian style into the Viennese playing style means incorporating slightly rougher articulation, too, but still in a very acoustic and resonant way. There’s nothing ever metallic, there’s nothing ever bombastic. As you know, Schmidt’s music can get quite loud, for instance at the end of the Second Symphony, or in the two catastrophe moments in the Fourth Symphony but there’s never a loss of quality in the sound otherwise the harmonic tension of the piece is destroyed.

If you imagine playing a piano, you can play louder and louder and louder, and at a certain point the strings stop resonating fully. There’s certain music which really plays with these sounds that you then get at this point: some contemporary music, but also some old music, for instance Mahler is interested in this extreme area – let’s call it “the not-beautiful”. Schmidt never quite hits anything that’s this extreme in the creation of the sound. There is trauma in what he’s writing about, but not in the instrumental colouring.

What would you say as a conductor are the specific challenges of Schmidt’s writing for orchestra?

Well for all the players it’s ferociously difficult to play. He writes very difficult music to play, but never too difficult. There is this joke that he wrote the Second Symphony to challenge his colleagues in the Vienna Philharmonic. Whatever the truth in that, it is very much on the limit, but yet it is never difficult for purely virtuoso reasons. It’s a bit like Clara Schumann said about Schumann’s music that there is no such thing as passage work in Schumann. It’s the same with Schmidt!

You have to train and rehearse the orchestra, so that these immense difficulties of playing are never heard as difficulties and can be nuanced and phrased and coloured to the same degree as a very simple line in a Haydn symphony.

Another challenge is… although I don’t know if it’s really a difficulty… one of the opportunities that Schmidt gives is that there is very little written in the score. It looks like a Mozart score: There are some dynamics, mostly piano to forte, some ‘mezzo’ dynamics, some crescendos, occasionally fortissimos… The same with tempos: one tempo marking almost per movement – of course the Fourth Symphony has a few more, the variations in the Second Symphony have different tempos. But there is a lot of realising or comprehending that has to be done by the conductor – which is wonderful, because it involves fantasy and imagination: How can you color this, or build it in a slightly different way?

Balancing is not difficult per se, but needs real work and care taken over it, because, again, much of the musical drama or the musical function of any moment comes from the bass line and middle voices, not the melody line. So you have to be able to hear and react to the inner voices, meaning that you might have a single note in the melody which has to change color because of something that’s happening in the violas.

The finding of the sound takes some time in rehearsals (and is very important), the finding of the gestures and the way they function and lead on to each other, without ever becoming too contrite. Schmidt’s music should never sound like the conductor is making choices, it should always sound like the music is demanding the choices itself, or that every choice that is made comes out of the music.

I suppose the the real job of a conductor in the performance of the Schmidt symphonies is about connecting the moment and making it cultured and varied, graceful and nuanced without ever losing track of the whole. So you ask yourself where you’re going, what the function of this moment is within the larger moment of the symphony, because it is deeply architectural structured music, there is no improvisation within Schmidt’s music, its all planned and constructed.

We are surrounded here by Schmidt’s Oriental Furniture [the original furniture of Schmidt’s living room, now situated in the Franz Schmidt Musikschule], and so it’s not too out of place to talk about what I’ve learned from Eastern philosophies and Japanese ideologies: That there’s an idea that two things, which are often seen as contrasted, opposites or dichotomies can be combined to be held under the same singular idea. In Schmidt’s music everything is always objective and subjective, everything is always thought through, created, built and constructed, and it is also felt, emotional, dramatic, storytelling, and if you, as a conductor, or a performer, or a musician, can find a way of drawing those together in the moment of performance – that moment might be 45 minutes long – you’re on to something.

Of course, Schmidt lived in this Viennese Jugendstil sphere, with all these ornaments and floral structures. But when you compare his scores with their sparse articulation and dynamic marks with Mozart, would you say that in his music there is a classical, or even baroque spirit below a Fin-de-siècle surface?

100%! As a comparison you can look at Viennese architecture, at Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos. People often see them as opposites. So Wagner is the ‘floralist‘, the artist of the surface, and Loos is the enemy of ornament, but they are still examples of the same underlying structures. Loos is really opposed to ornaments, but yet the balance, lines and the structures he creates are beautiful, Wagner still has to build buildings that stand and with beautiful lines and structures all in balance, even if they have surface ornamentation.

As an aside, something I love about Otto Wagner’s creations is that things are individual. So you look at a set of windows, which from a distance look all like they have the same motif, but over the six windows there is still a progression one way or another, so there is still an understanding of the structure. And look at his railings! I know, I’m a musician, I shouldn’t be talking about railings, but I find them fascinating.

The railings are not in the style of American minimalism in pattern, they change and they shape; it must have been so expensive to make them (Wagner never takes the cheap of easy option). It’s sort of anti-industrial-revolution, against the thinking of everything has to be the same.

In Vienna between 1890 and 1930 there is this conjoining of architectural structure and ornament. The ornament must be so much part of the structure that it is unseen as an ornament as is the case in both Loos and Wagner but in very different degrees. One of the great examples in literature is Heimito von Doderer, a complex personality with a complex relationship to history. He wrote one of the most highly constructed books, where the structure of the book is meant to represent Die Strudlhofstiege, where you take elongated routes to get to your destinations (again never the easiest of simplest route). Its very ornamented, nothing ever goes in straight lines, and things cross over, but all important moments happen on the steps. I think that Schmidt is absolutely in the heart of that movement. Look at Schoenberg, who’s seen as a modernist – and I’m not saying he wasn’t –, but what is Erwartung or the Sechs kleine Klavierstücke if not a representation of the idea that things should never be the same which is an ideal that Schmidt absolutely stood by.

When I perform Schoenberg I treat him as I treat Schmidt. Of course, in Schoenberg there’s the modernist things and the ideology and the construction of a new framework, but actually that all comes out of a gravitational and contrapuntal thinking where every note has to create the next. When you compare Webern with Schmidt’s Fourth Symphony, you see that Schmidt and Webern occupy a very similar world much like Loos and Wagner.

It you think of the compositions of Franz Schmidt, which would you think would be a good example to introduce this composer to a person who does not yet know his music?

Well, I think the ‚correct’ answer is the slow movement from the Fourth Symphony, because of its approachability. It is something quite concrete: a funeral march with a moment of grief, then a moment of anger, and then a moment of grief returning, which has been changed by the anger. It’s phenomenal music. You follow it, you can’t not get caught up in it. That is a wonderful place to start! However, I think if you start there you might love that, but you might still need to make a jump to the rest of his music, because Schmidt’s music is so created to go from the very beginning to the very end of a symphony, and the apparent concreteness or extra musical ideas behind this second movement are not very present in Schmidt’s other music. So I think, if you enter Schmidt’s music from that point, and you look for this special kind of expression in other pieces of Schmidt, you might be disappointed.

I would really encourage to give yourself 46 minutes, lock the front door – maybe you are with some friends, maybe you’re not –, take a nice glass of wine or whiskey, sit in your most comfortable chair, put on the best headphones or speakers or sound system that you can, and play the Fourth Symphony from the beginning to the end. If you commit 46 minutes to that, you will never go back. I don’t want to say it will change your life – because you’re not going to suddenly grow six feet, or lose weight, and there’s not going to be World Peace –, but your experience of music and of Schmidt will have been changed, and, I think, you will be rewarded for it.

So, if someone never has heard Schmidt: sit down and listen the 46 minutes of Symphony No. 4.

Are there other composers, you can imagine to do the same for them as you did for Schmidt?

Very simply, yes! We are thinking at the moment to do another project with Accentus Music, and we are looking at what that might be. I won’t mention anything yet, because we are in the process of thinking about it, but I am very clear that it must fulfil many of the same criteria. Any new recording must be meaningful and it must be needed. I have no interest in doing something just for me; actually, I don’t want it to be about me – the Franz Schmidt Project was about the Franz Schmidt Symphonies, not about me.

I think there is a lot of music that’s not very well known, and not very often played and that there is great, great need to diversify in classical music programming. We must really find things off this central line, we must find things to believe in and really stand behind, because they are imaginative, honest, daring, vulnerable, fragile. The music that I am attracted to has all of those qualities. So yes, there will be another project!

Thank you very much for this conversation!